A New Mandate of Heaven?

Nationalism and Chinese space policy.

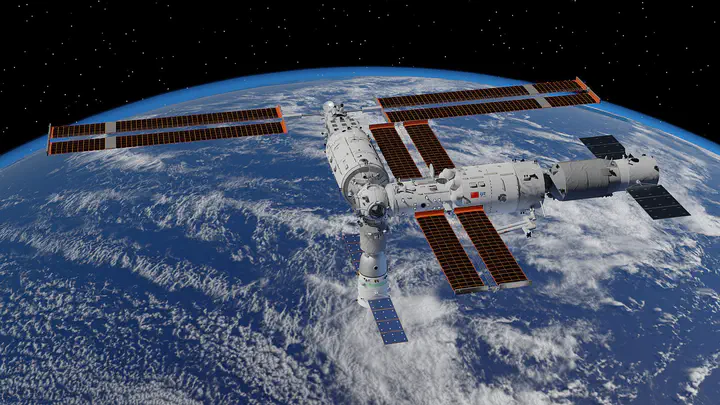

Image Credit: Shujianyang

Image Credit: ShujianyangMore than fifty years after the conclusion of the Space Race, the United States again finds itself locked in an interstate conflict over hegemony in outer space. This time, however, the opponent is a rising China, which has aggressively invested in outer space exploration and development.1 Given the high stakes of this new space race, this paper seeks to interrogate the past, present, and future of Chinese space programs. First, I describe the explosion of China’s space sector and attempt to discover the root cause behind this growth. To this end, I evaluate three potential explanations: an expansion of military dominance, a pursuit of economic gain, and an exhibition of national pride. Next, I assess the prospects for future cooperation and competition between the United States and China in outer space, finding that while broad agreement is unlikely, narrow partnerships based on shared interests are viable.

China has maintained a small space program since 1956, when Quian Xuesen, the so-called “father of Chinese rocketry,” spearheaded the construction of the nation’s first missiles.2 After the ascension of Deng Xiaoping, the program pivoted away from missiles; Deng executed a major restructuring of China’s space agencies with a focus on commercial satellites. Through this platform, China launched 29 satellites into orbit and began to export satellites to other countries as well.2 Despite these early attempts, China’s first true efforts to build a modern space sector have occurred after the turn of the twenty-first century. During Xi Jinping’s tenure in particular, Beijing has poured resources into space development at an unprecedented rate. In 2022, for instance, government expenditures on space were close to $12 billion, second only to the United States.3 What, then, are the underlying motives behind this aggressive expansion?

One possible explanation stems from China’s military interests in outer space. The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has developed a wide array of weapons dedicated to use in space. Chief among them are anti-satellite weapons, which can knock satellites out of orbit through physical contact or directed energy. In 2007, China conducted a now-famous test of an anti-satellite weapon, and has since conducted research into more advanced weaponry.4 Critically, many American satellites provide essential military services, including nuclear sensor systems, and a single attack could generate spillover effects as entire constellations of satellites are hit by the resulting debris.5

China has also developed an advanced navigation system, Bei Dou, to augment its war planning capabilities. This system relies on a constellation of satellites which can send and receive location information across a battlefield, an ability that is particularly useful for precision-guided missile strikes.6 Chinese satellites also serve a variety of other military purposes, with 14 dedicated to command and control while 32 focus on reconnaissance.2 Cyberwarfare is important as well, and China has strengthened its capacity to stage cyber and electronic attacks against targets in space.7

Notably, the space program has involved collaboration between actors in the PLA, the Central Military Commission (CMC), and the commercial sector, contributing to what is often termed civil-military fusion, or junmin ronghe. Along with tech-heavy industries such as quantum computing and semiconductors, China has focused on recruiting scientific talent to research dual use-technology in the aerospace industry.8 Lorand Laskai argues that civil-military fusion occurs as a bidirectional process: on the one hand, the PLA and CMC share military technology with private companies for commercial use, and on the other, the same private companies produce defense equipment for PLA use.9 Still, though, this is an unequal partnership. The CMC maintains complete control over the approval process for commercial space launches and state-owned defense companies remain dominant.9 Suisheng Zhao expands on Laksai’s analysis and points to increasing integration within the military itself, as Xi Jinping has tightened the Communist Party’s grip over the military. In contrast to the lax attitudes of Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao, Xi handpicked members of the CMC, reasserting his role as the chair of the commission, and oversaw a reorganization of the PLA.1011 Rush Doshi concurs, noting that Xi has made space one of his core military priorities, along with the poles and the deep sea.12 Civil-military fusion in the space sector is thus both materially important in accelerating the development of technology and perceptually important in Xi’s effort to cement his control over the PLA and private enterprise.

Another compelling rationale for China’s blossoming space policy is economic: China views outer space as a vital domain for facilitating the transition to a digital future. For instance, the aforementioned Bei Dou navigation system is more than a military venture; it is perhaps even more salient for Beijing’s economic ambitions. Many view Bei Dou as a competitor to the United States-run Global Positioning System (GPS), which dominates the global navigation market.13 By displacing GPS, China hopes to facilitate regional economic integration through the provision of a package deal that includes both navigation and other forms of infrastructural support. Indeed, Bei Dou dovetails nicely with the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), as the system already covers more than 30 countries in the BRI, including strategically important partners such as Pakistan and Indonesia.6 Chinese officials have referred to Bei Dou as the “digital glue” of the BRI, facilitating remote sensing, imaging, and precise location tracking for industries such as agriculture and financial services.14

More speculatively, China has explored the prospect of asteroid mining for key minerals, planning the Tianwen-2 launch to collect samples from the small near-Earth asteroid Kamo’oalewa.15 NASA administrator Bill Nelson remarked in a recent interview that China could use scientific research as an excuse to establish a mining base on the moon as well, citing Chinese aggression in the South China Sea as an example.16

In recognition of these economic opportunities, China has cajoled a domestic space industry into existence. Before Xi Jinping took office in 2014, China’s space programs were dominated by two state agencies: the China Aerospace Science & Industry Corporation Limited and the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation. As technology developed and the cost of satellite launches plummeted, however, the government became increasingly interested in encouraging private sector growth.17 To that end, it issued a directive, Document 60, which opened the door to private investment in space firms. In the next five years, over 40 corporations began operating in the sector, a trend welcomed by the Xi administration.18

Despite these advances, China’s private space economy remains nascent at best, especially when compared to its Western counterparts. As of 2019, only one Chinese company, i-Space, had successfully completed a satellite launch, while the American SpaceX had launched 81 successful missions on its own.19 Contributing to this disparity is China’s lack of a national space law, which leads to regulatory murkiness for startups hoping to enter the market, along with harsh American export controls which make it difficult for Chinese companies to receive key astronautical technologies.20

In response to these export controls, Chinese firms have sought to distance themselves from the government, insisting that they are independent entities and pushing for foreign investment.17 In doing so, they attempt to walk a thin line between preserving the government’s support and rejecting government influence, a task made more difficult by Xi’s emphasis on civil-military fusion. Other Chinese companies have taken a different path, choosing instead to build indigenous sources for astronautical equipment that they cannot import from abroad. This tactic, one cemented in China’s 2006–2020 Medium- and Long-Term National Science and Technology Development Plan, could lead to a broader decoupling of space supply chains in the future.18

The last and most important reason for China’s recent space boom is nationalism. In both rhetoric and action, Beijing has used outer space as a measuring stick to display its scientific prowess and rising superpower status. China’s 2021 white paper on space exploration drives this home with language specifically focused on national rejuvenation: “The mission of China’s space program is… to raise the scientific and cultural levels of the Chinese people, protect China’s national rights and interests, and build up its overall strength”.21 The nomenclature of Chinese spacecraft reflects this same message, as the Tiangong (“Heavenly Palace”) space station and Long March launch vehicles capture the vibrant history of the country.

On a more concrete level, China has invested heavily in human spaceflight, a realm with few military or economic applications.22 Indeed, China spends a full third of its space budget on human spaceflight, more than any other country.23 This suggests that military or economic rationales for space development, while present, are not the driving force behind the majority of China’s space program. Xi Jinping’s pursuit of the Tiangong space station is of particular interest. Because of the 2011 Wolf Amendment, NASA is unable to cooperate with China on space-related matters, meaning that Chinese taikonauts cannot participate in the International Space Station.24 Undeterred by this roadblock, China has ambitiously pursued a space station of its own, completing the Tiangong last November. The development of its own space station allows China to lease space to other nations to conduct scientific experiments in low Earth orbit, which is especially important given that the International Space Station is due to be decommissioned in 2030.25 In a related vein, China launched plans for the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS) in 2016 as a direct competitor to the United States-led Artemis Program.26 Both endeavors aim to establish a long-term human presence on the moon by engaging the international community, so China’s embrace of the ILRS allows it to present itself as a superior national power.

Beijing has heavily promoted their achievements in space to the Chinese populace, turning launch sites on the Hainan coast into tourist destinations that echo Cape Canaveral.27 By putting space missions in the spotlight, China paints itself as a techno-nationalist state with scientific achievement as a benchmark for national glory.28 Early indications are that this propaganda has been successful; the Chinese populace is broadly supportive of human spaceflight missions despite their cost.29 Similarly, China has leveraged international coalitions to spread this nationalist message, engaging the Shanghai Cooperation Organization to promote its outer space militarization efforts.12 China recognizes that space exploration can be a potent soft power tool to sway nations, just as it was during the Cold War.

With China’s multifaceted motives for space exploration in mind, this paper now turns to the question of future cooperation. Past treaties governing outer space, notably the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, set broad guidelines for the use of space resources and pushed for demilitarization.30 However, these treaties were voluntary and nonspecific, making it difficult to enforce their provisions for signatories. Furthermore, this framework has failed to adapt to the emergence of new technologies and a multipolar environment. The shortcomings of the Outer Space Treaty beg the question: can China and the United States set aside great power competition on Earth to work together on the interplanetary stage? Unfortunately, it seems that the prospects for a landmark space agreement are slim at best for a few reasons.

Principally, there exists little precedent to work off of for an international agreement. While the United States and China are both signatories to the major UN treaties on space, the writing of those treaties was governed largely by the United States and Soviet Union. China’s hesitation to engage in negotiation may wane, however, as it has much more to lose now from a confrontation in space than it did a decade ago. Other barriers to cooperation include a general sense of mistrust and suspicion, the complexity of navigating the security dilemma, the distance created by the Wolf Amendment, and allegations of illegal technology transfers and theft.5

However, given that China and the United States share some areas of common interest, narrow cooperation in outer space is possible. For instance, during the Obama administration, officials in both countries set up a “space hotline” to share information and reduce the risk of collisions.5 In the present day, one possible cause for consensus is a ban on anti-satellite weapons testing. In his confirmation hearing, John Plumb, the top Pentagon official for space policy, voiced support for such a ban, and expressed optimism that a new United Nations working group on common norms in space might bring China and Russia to the table.31 These are more than empty promises: the Biden administration announced a self-imposed, unilateral moratorium on direct-ascent anti-satellite missile tests.32 On the Chinese side, Beijing submitted the (lengthily-titled) Treaty on the Prevention of the Placement of Weapons in Outer Space and of the Threat or Use of Force Against Outer Space Objects to the United Nations in 2021. The treaty seeks to ban the placement of weapons in outer space, but it has failed to gain Western support because it contains loopholes designed to weaken compliance requirements for China and Russia.33 Still, the fact that China is willing to engage in, and even lead negotiations over anti-satellite weapons should be celebrated given their past reluctance to do so.

Another potential area of compromise is the issue of space debris. There are over 29,000 manmade objects in orbit around the Earth, and the vast majority of these objects are no longer operational satellites.34 Most of this debris is clustered in low earth orbit, where telecommunications and navigation satellites fly, meaning that any potential collision could cause a cascading drop in service.34 To navigate these dangers, spacefaring nations rely on publicly-available data produced by the United States Space Command, but this information is often inadequate and incomplete.32 Sharing private data on satellites could prove mutually beneficial for both the United States and China, which means that a narrow treaty in this area has the potential for success.

In reviewing the many drivers of recent Chinese space development, it becomes clear that while military and economic factors are significant, nationalism is the ultimate engine that drives the Chinese space program forward. Furthermore, while the outlook for broad United States-China cooperation in outer space may be dour, diplomats on both sides of the Pacific can still make meaningful gains on the margins. As the United States and China look to avoid a new Cold War, policymakers should remember the importance of space, an increasingly critical domain in a broader great power competition.

Pekkanen, Saadia M. “Governing the New Space Race.” AJIL Unbound, vol. 113, 2019, pp. 92–97., doi:10.1017/aju.2019.16. ↩︎

Chandrashekar, S. China’s Space Programme: From the Era of Mao Zedong to Xi Jinping. Springer Nature, 2022. ↩︎

Euroconsult. “Government Expenditure on Space Programs in 2020 and 2022, by Major Country (in Billion U.S. Dollars).” Statista, Statista Inc., 31 Dec 2022, ↩︎

Glaese, Oskar. “China’s Directed Energy Weapons and Counterspace Applications.” The Diplomat, 29 June 2022, thediplomat.com/2022/06/chinas-directed-energy-weapons-and-counterspace-applications. ↩︎

MacDonald, Bruce, et al. “China and Strategic Instability in Space: Pathways to Peace in an Era of US-China Strategic Competition.” United States Institute of Peace, 9 Feb. 2023, www.usip.org/publications/2023/02/china-and-strategic-instability-space-pathways-peace-era-us-china-strategic. ↩︎

Jakhar, Pratik. “How China’s GPS ‘Rival’ Beidou Is Plotting to Go Global.” BBC News, 20 Sep. 2018, www.bbc.com/news/technology-45471959. ↩︎

Campbell, Caitlin. China’s Military: The People’s Liberation Army (PLA). Congressional Research Service, June 2021. R46808. crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R46808/3. ↩︎

“The Chinese Communist Party’s Military-Civil Fusion Policy.” U.S. Department of State, 2017-2021.state.gov/military-civil-fusion/index.html. Accessed 26 May 2023. ↩︎

Laksai, Lorand. “Building China’s SpaceX: Military-Civil Fusion and the Future of China’s Space Industry.” Testimony before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission Hearing on China in Space: A Strategic Competition?, 4 May 2019, www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/Lorand%20Laskai%20USCC%2025%20April.pdf. ↩︎

Zhao, Suisheng. Dragon Roars Back: Transformational Leaders and Dynamics of Chinese Foreign Policy. Stanford University Press, 2022. ↩︎

Wuthnow, Joel, and M. Taylor Fravel. “China’s Military Strategy for a ‘New Era’: Some Change, More Continuity, and Tantalizing Hints.” Journal of Strategic Studies, Mar. 2022, pp. 1–36, https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2022.2043850. ↩︎

Doshi, Rush. The Long Game. Oxford University Press, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780197527917.001.0001. ↩︎

Dotson, John. “The Beidou Satellite Network and the “Space Silk Road” in Eurasia.” Jamestown Foundation, 15 July 2020, jamestown.org/program/the-beidou-satellite-network-and-the-space-silk-road-in-eurasia/ ↩︎

Chase, Michael. Securing the Belt and Road Initiative: China’s Evolving Military Engagement Along the Silk Roads. The National Bureau of Asian Research, Sep. 2019. NBR Special Report 80. www.nbr.org/wp-content/uploads/pdfs/publications/sr80_securing_the_belt_and_road_sep2019.pdf. ↩︎

Jones, Andrew. “China to Launch Tianwen 2 Asteroid-Sampling Mission in 2025.” Space.com, 18 May 2022, www.space.com/china-tianwen2-asteroid-sampling-mission-2025-launch. ↩︎

Helmore, Edward. “‘We’re in a Space Race’: NASA Sounds Alarm at Chinese Designs on Moon.” The Guardian, 2 Jan. 2023, www.theguardian.com/science/2023/jan/02/china-moon-nasa-space-race. ↩︎

Patel, Neel. “China’s Surging Private Space Industry Is Out to Challenge the US.” MIT Technology Review, 21 Jan. 2021, www.technologyreview.com/2021/01/21/1016513/china-private-commercial-space-industry-dominance. ↩︎

Liu, Irina, et al. Evaluation of China’s Commercial Space Sector. Institute for Defense Analyses, Sep. 2019. D-10873. www.ida.org/-/media/feature/publications/e/ev/evaluation-of-chinas-commercial-space-sector/d-10873.ashx. ↩︎

“How Is China Advancing Its Space Launch Capabilities?” Center for Strategic and International Studies, 5 Nov. 2019, www.csis.org/analysis/how-china-advancing-its-space-launch-capabilities. ↩︎

Peng, Zhang. “The Space Law Review: China.” The Law Reviews, 5 Jan. 2023, thelawreviews.co.uk/title/the-space-law-review/china ↩︎

“Full Text: China’s Space Program: A 2021 Perspective.” The State Council of the People’s Republic of China, 22 Jan. 2022, english.www.gov.cn/archive/whitepaper/202201/28/content_WS61f35b3dc6d09c94e48a467a.html. ↩︎

Koren, Marina. “China’s Growing Ambitions in Space.” The Atlantic, 23 Jan. 2017, www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2017/01/china-space/497846. ↩︎

“What’s Driving China’s Race to Build a Space Station?” China Power Project, 21 Apr. 2021, chinapower.csis.org/chinese-space-station. ↩︎

Weeden, Brian, and Xiao He. “US-China strategic relations in space.” Avoiding the ‘Thucydides Trap’. Routledge, 2020. 81-103. ↩︎

Kuo, Mercy. “The Politics of China’s Space Power.” The Diplomat, 14 June 2021, thediplomat.com/2021/06/the-politics-of-chinas-space-power. ↩︎

Wu, Xiaodan. “The International Lunar Research Station: China’s New Era of Space Cooperation and Its New Role in the Space Legal Order.” Space Policy (2023): 101537. ↩︎

Wen, Allen, et al. “How Hainan Is Parlaying Space Tourism Into Populist Support.” Bloomberg, 15 May 2023, www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2023-05-15/hainan-island-space-tourism-shows-support-for-china-s-space-ambitions. ↩︎

Wang, Zheng. “National Humiliation, History Education, and the Politics of Historical Memory: Patriotic Education Campaign in China.” International Studies Quarterly, vol. 52, no. 4, 2008, pp. 783–806. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/29734264. Accessed 26 May 2023. ↩︎

Hines, R. Lincoln. “Heavenly Mandate: Public Opinion and China’s Space Activities.” Space Policy, Jan. 2022, p. 101460, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spacepol.2021.101460. ↩︎

Kimball, Daryl. “The Outer Space Treaty at a Glance.” Arms Control Association, Oct. 2020, www.armscontrol.org/factsheets/outerspace. ↩︎

Hitchens, Theresa. “Biden’s Space Policy Nominee Backs Ban on Destructive ASAT Testing, Pushes Norms - Breaking Defense.” Breaking Defense, 13 Jan. 2022, breakingdefense.com/2022/01/bidens-space-policy-nominee-backs-ban-on-destructive-asat-testing-pushes-norms. ↩︎

Ligor, Douglas. “Reduce Friction in Space by Amending the 1967 Outer Space Treat.” War on the Rocks, 26 Aug. 2022, warontherocks.com/2022/08/stabilize-friction-points-in-space-by-amending-the-1967-outer-space-treaty. ↩︎

Bowman, Bradley, and Jared Thompson. “Russia and China Seek to Tie America’s Hands in Space.” Foreign Policy, 31 Mar. 2021, foreignpolicy.com/2021/03/31/russia-china-space-war-treaty-demilitarization-satellites. ↩︎

Miraux, Loïs. “Environmental Limits to the Space Sector’s Growth.” Science of the Total Environment, vol. 806, Feb. 2022, p. 150862, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.150862. ↩︎