Charting a New Path for Latin America

Foreign policy recommendations for the United States.

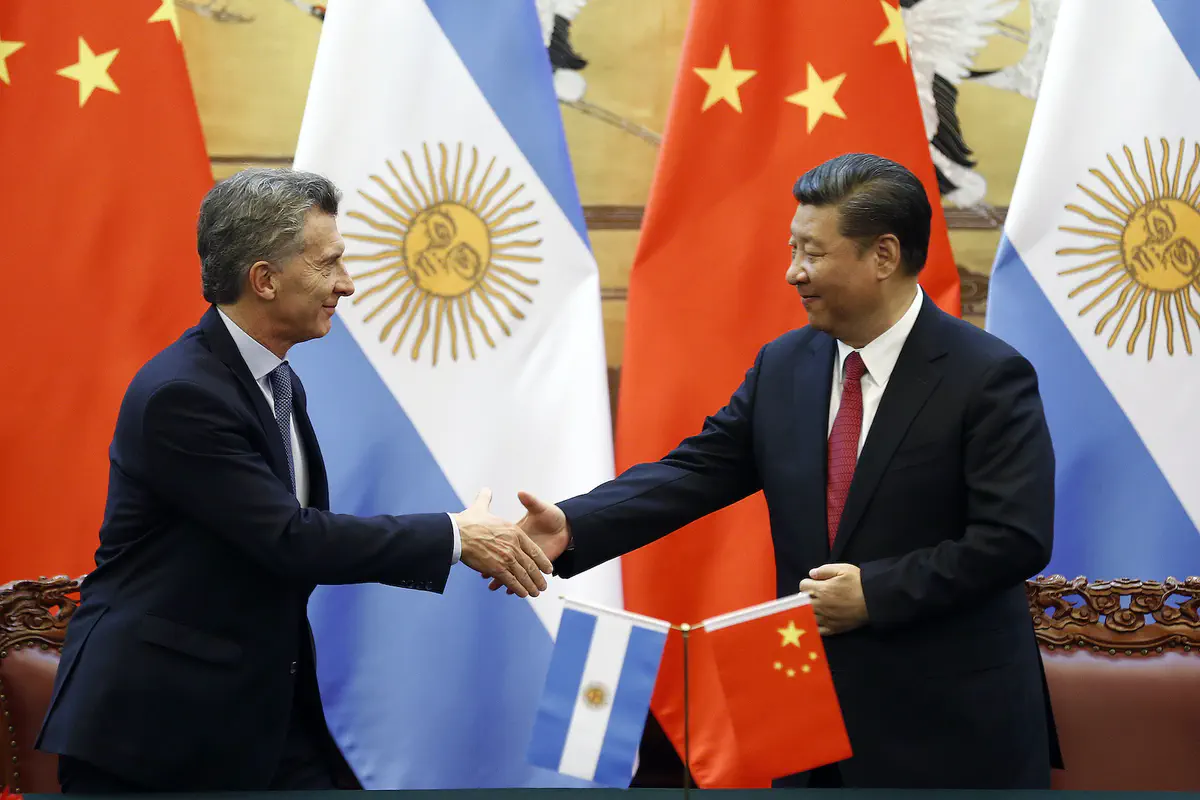

Image credit: Damir Sagolj/Getty Images

Image credit: Damir Sagolj/Getty ImagesIncreasingly, scholars frame global relationships through the lens of great power competition—a sprawling battle between the United States on one side and China and Russia on the other. This tension has heightened during the first two years of the Biden administration, with Russia’s war in Ukraine and China’s belligerence over the Taiwan Strait attracting international condemnation. While these threats are distant, the American answer to these provocations lies right next door. Renewed engagement in Latin America represents a key step towards winning the great power competition and maintaining the United States’ global hegemony.

Principally, policymakers should recognize that both China and Russia have made significant inroads in Latin America. Under Xi Jinping, China has aggressively pursued trade ties with Latin American nations, to the point where China is now the primary trade partner of Peru, Chile, Uruguay, Argentina, and Brazil. This trend is both widespread and rapid: Chinese trade with the region has grown from just $12 billion in 2000 to over $315 billion in 2019.1 Through its flagship Belt and Road Initiative, Beijing has targeted investments into infrastructure and technology, expanding the reach of state-owned enterprises such as Huawei and Tencent. Russia’s influence, on the other hand, is primarily in the security sector; the nation has regularly provided military aid to Cuba, Nicaragua, and Venezuela with the hopes of propping up dictators in each country.2

These intercontinental linkages represent short-term opportunities for Russia and China and long-term challenges for the United States. China’s arrival in Latin America, far from fostering economic liberty, has led to financial dependence from cash-strapped states.3 Already, China has used the promise of its investment to twist the arm of Nicaragua and the Dominican Republic; both nations relinquished their recognition of Taiwan as a sovereign state in exchange for loan packages from China.4 Similarly, the Kremlin has flexed its military might to prevent Latin American states from voicing their disapproval of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Thus, the growing role of Russia and China in Latin America is a two-headed monster. First, the support of these powerful regimes entrenches authoritarian leaders, offering them institutional support in the face of American pressure. Secondly, those same authoritarians provide legitimacy, resources, and strategic backing to China and Russia.

Therefore, American policy in Latin America must focus on winning back states that hover in the balance between democracy and authoritarianism, which means doubling down on democracy promotion efforts in the region. By investing in regional infrastructure, vaccine diplomacy, and international organizations such as the Organization of American States, the United States can reassure its allies of its commitment and combat growing autocratic influence. These efforts should be focused on the shared priorities of the Americas: stable economic development, environmental sustainability, and regional security.

Notably, continued instability in Latin America creates risks not only in the broad scheme of great power competition, but also in decidedly domestic terms. For example, political and economic crises in Haiti, Venezuela, and Nicaragua, among other countries, have fueled a growing migrant crisis at the Southern border of the United States. In fiscal year 2022, migrant apprehensions at the border reached 2.4 million—an all-time high.5 The Biden Administration’s policy through its first two years has been a focus on root causes of migration, including several high-profile commitments to fresh humanitarian and economic development initiatives at the June 2022 Summit of the Americas.

However, the Biden administration continues to receive pushback from Congressional Republicans on these policies, largely because of calls for a return to Trump-era punitive actions to deter migration. Framing engagement with Latin America in terms of global hegemony, rather than the contentious immigration debate, may produce more fruitful consensus on foreign policy issues. In the context of the recent midterm elections, which produced divided government and portend legislative difficulties ahead, bipartisan foreign policy is more important than ever.

Latin America, long neglected and exploited by world powers, may prove to be the tipping point in this century’s great power competition. China and Russia have long been cognizant of this fact, and it time for the United States to take note.

Mark P. Sullivan and Thomas Lum, “China’s Engagement with Latin America and the Caribbean,” Congressional Research Service, June 1, 2020, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/IF10982.pdf. ↩︎

Evan Ellis, “Russia in the Western Hemisphere: Assessing Putin’s Malign Influence in Latin America and the Caribbean,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, July 20, 2022, https://www.csis.org/analysis/russia-western-hemisphere-assessing-putins-malign-influence-latin-america-and-caribbean ↩︎

“Aid from China and the U.S. to Latin America amid the COVID-19 crisis,” Wilson Center, April 29, 2022, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/aid-china-and-us-latin-america-amid-covid-19-crisis. ↩︎

Lily Kuo, “Taiwan loses another diplomatic partner as Nicaragua recognizes China,” The Washington Post, December 10, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/nicaragua-taiwan-china/2021/12/09/741098d8-5954-11ec-8396-5552bef55c3c_story.html ↩︎

Mark P. Sullivan, “Latin America and the Caribbean: U.S. Policy Overview,” Congressional Research Service, November 23, 2022, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/row/IF10460.pdf ↩︎