Matt Clancy on Patents, Progress, and the Power of Science

My interview with Matt Clancy of Open Philanthropy

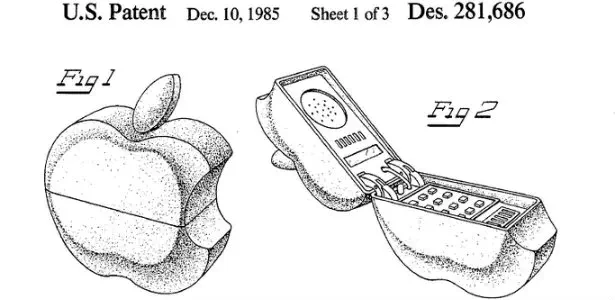

Image Credit: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office

Image Credit: U.S. Patent and Trademark OfficeOn April 3, 2024, I had the pleasure of interviewing Matt Clancy, an economist and Research Fellow at Open Philanthropy. Matt is the creator and sole author of New Things Under the Sun, a living literature review on academic research about science and innovation. You can find the interview here:

For reference, I’m also including the questions I had planned for the interview, some of which I didn’t get to ask because of time constraints.

Orienting / General Questions

To kick us off, I’m curious about what drew you to the field of innovation and progress in the first place. As an economist, you develop a set of tools that are applicable to a wide range of fields and questions. Why focus on innovation in particular?

- Follow-up: The crossover between economics and progress studies seems relatively clear. Are there any academic disciplines that you think have something to say about progress and might be overlooked? (This question is motivated by the section of New Things Under the Sun where you solicit “living literature reviews on neglected topics that are relevant for policy-making”).

Another framing question, which I’ll keep purposely broad: what does progress mean to you?

One challenge with regulating emerging technologies is that often the few people who understand these technologies well enough to regulate are those in industry. This concern is particularly relevant in the case of AI, where many of those contributing to legislation, including Biden’s recent executive order, are members of the tech industry. Does this insider access worry you, and how do you think we ought to draw on the technical expertise of AI companies without incorporating potential bias into policy?

One of your grantmaking priorities at Open Philanthropy is “investigating programs and policy reform to help more migrants, especially highly-skilled migrants, move to countries operating on the scientific and technological frontier.” I have two questions about this funding stream:

- First, Doran, Gelber, and Isen find in a recent paper analyzing H1-B visa lotteries that winning a lottery for a skilled foreign worker crowds out otherwise available workers and does not increase firm patenting. They further conclude that winning these lotteries has little effect on either firm innovation or growth. How do these findings square with the theory of change of your grantmaking on immigration?

- Second, I’m curious about the political viability of your approach, which centers on opening new doors for highly-skilled migrants. How do you think this focus meshes with the broader pro-immigration push, which is often focused on low-income migrants from Latin America who flee violence or poverty? Do you believe there is a trade-off between these two groups of migrants, or could advocating for high-skilled immigration lead to greater acceptance of other groups’ immigration?

New Things Under the Sun

As an economics student, I was fascinated by your article “How a field fixes itself: the applied turn in economics.” In the article, you wrote about how policymakers applied external pressure to academic economists to encourage the use of data and randomized control trials. As you note, this pressure is somewhat unique to economics, and doesn’t fix many of the other issues that plague the field.

- What do you see as the next frontier for social science research? Are there other fields that you think are primed for a revolution similar to the one economics has experienced?

- Especially in the natural sciences, funding for research often comes from federal funders like the NIH and NSF. To what extent do partisan politics affect the functioning of these agencies? Are there specific issues related to science and the 2024 elections that you’re tracking?

One of the core questions of Pathways to Progress is how to measure progress. In the recent “Can We Learn About Innovation From Patent Data?” article, you write about the promise and limitations of patents as a metric for innovation. Can you speak briefly to what you found, and what alternative methods of measuring progress you might turn to?

You’ve written both in New Things Under the Sun and in popular media about the potential of remote work to support innovation. As part of that work, you’ve pointed in particular to the fading advantages of cities when it comes to things like knowledge repositories, team formation, and market size. For instance, as you note, academia is a successful example where coauthors on papers are now commonly located on campuses thousands of miles apart. Two questions here:

- First, to what extent does this argument apply across industries? It may be true in particularly knowledge-intensive fields like economics, where you can send PDFs all day long, but in a sector where physical proximity is critical—say, pharmaceutical research—is remote work still a viable model for innovation?

- Second, I’m curious about the implications of this argument on cities themselves. Finding a common space to innovate seems like one of the core motivators for forming cities in the first place. If, as you argue, remote work can supplant that function, what role will cities play in society in 20, 50, or 100 years? Do they need to exist at all?

In “What if we could automate invention?” and a debate you conducted with Tamay Besiroglu, you talked about potential barriers to explosive growth resulting from AI. Among those are shortages of critical materials, a lack of training data, and regulatory obstacles. In the 10 months since this debate was published, a lot has happened in the AI space, and I’m curious how your thinking has changed, if at all. Do any of those bottlenecks now strike you as particularly problematic on the path to growth?

- Even though you’re doubtful about the potential of explosive growth, I still think it’s worth talking about what a world with explosive growth would look like. Conditional on explosive growth happening, what do you think the distributional effects of that growth would be? In other words, will the average person receive welfare gains from AI-generated growth?

“The Returns to Science In the Presence of Technological Risks”

- One challenge with estimating utility in the long-term future is that the value systems of future humans may be very different from our own. I think one good heuristic to understand this idea is that we see many practices of the past, such as human sacrifice or bloodletting, as abhorrent or absurd. With that in mind, it seems difficult to estimate what future human preferences will look like, and as a result, to predict how science will affect their utility. How do you attempt to grapple with shifting preferences in your paper?

- Lizka Vaintrob asked (paraphrasing): Why focus specifically on biotech? I expect that it’s usually good to narrow the scope of reports, but why not include risks from AI?

- Corentin Biteau asked: “Did you try looking at animal welfare when calculating for the overall utility of science? I expect this could substantially change your results, especially when including the many ways technological progress has been used to boost factory farming (e.g. genetic sélection).”

- In the conclusion to your paper, you write that the return to science is about 230x, or in other words, that investing a dollar in science has roughly the same effect on welfare as giving 230 people who make $50,000 one additional dollar. You’ve since revised this estimate down, but it still seems like a lot in absolute terms. Problems arise when comparing it to other estimates, however. Per Open Philanthropy, the cost-effectiveness bar for Global Health and Wellbeing spending is roughly 1100-1200x, or about five times greater than the return to science. With what seem to be much higher returns elsewhere, how do you justify spending on science?

- I was particularly intrigued by the section of the paper where you discuss the quality of science, as opposed to the quantity. It seems to me that the idea of “better” science encompasses two ideas: first, changing the kinds of technology that are produced, and second, in the case of dual-use technology, changing the ways in which technology is used. To the extent that the two are dichotomous, are you partial to either channel over the other as a path to improving the quality or safety of science?

- You summarize the model of Jones (2016), who argues that as a society grows richer it will rationally reallocate more of its R&D budget towards mitigating hazards rather than accelerating growth. How do collective action problems affect this reallocation? In other words, why should we trust private actors to fund a public goal, that is, hazard mitigation, rather than free riding?

Concluding Questions:

- Most of your work focuses on the determinants and societal effects of science, but I think there’s something wonderful about stopping for a second to appreciate technological discoveries in and of themselves. I wonder, is there a specific scientific discovery or technology that fascinates you in this way?

- The release of Oppenheimer last summer sparked, in my view, an enlightening discussion about the role of scientists in public and political discourse, as well as ways to manage risks from potentially catastrophic technology. Is there any media, particularly fiction, that captures well the way you think about progress?

- What advice would you offer to young people, either students or early-career professionals, who are interested in studying science and innovation? Are there any resources that you find helpful or opportunities that you would recommend?