What's in a Tiger?

War in the woodblocks.

Image Credit: Saint Louis Art Museum

Image Credit: Saint Louis Art MuseumOn Saturday, May 18, I gave a talk at the Smart Museum of Art about a woodblock print from the Meiji era as part of the exhibit Meiji Modern: Fifty Years of New Japan.

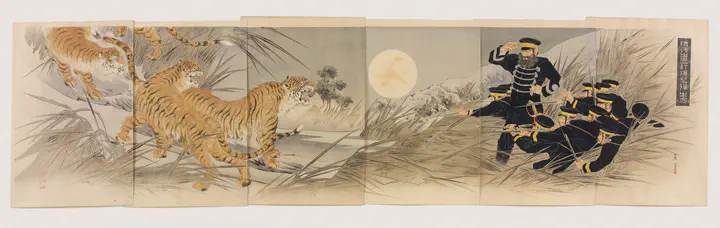

Hi, I’m Ethan! I want to talk about Mishima Shōsō’s wonderful piece, The Qing Army’s Foolish Plan of Using Tigers as Weapons, which I find fascinating because the Qing army almost certainly never used tigers as weapons. Even if it’s fictional, this image of a moonlit standoff offers us a window into the militarism of the Meiji period and the importance of propaganda in Japan’s development.

Let’s start with the soldiers that you see on the right. Anything you notice about these soldiers off the bat? At first, it might not be obvious that they are Japanese soldiers, which is a sign of how deeply Western culture had penetrated in Japan during this era. The soldiers are dressed in dark navy blue uniforms, with color and style similar to the French and Prussian armies. They’re wearing kepis, a French cap with a flat top and a visor. Call it Paris Fashion Week. The uniforms feature insignia with rank and regiment, aligning with Western military traditions. Most importantly, the soldiers are tightly grouped, disciplined and determined men who will obey their commander and stand together in the face of any danger.

Notably, the Japanese military seen in this image was rapidly changing. Before 1850, Japan had adopted a policy of sakoku, or national seclusion, for over 200 years. In 1854, however, American Commodore Matthew Perry sailed to Japan and, under threat of force, compelled Japan to sign the Kanagawa Treaty, which opened up Japan’s ports to foreign trade. This humiliation sparked a military modernization effort. Never again would Japan be so embarrassed. As part of that effort, Japan enlisted foreign military advisors, namely the French, began manufacturing weapons at scale, and launched a conscription program. It’s a little ironic that this effort to become more independent from Europe ended up making Japan a lot more like Europe. Interestingly, the modernization also brought about the end of the samurai and sparked a huge civil war between samurai and the new army.

But the opponent in this image is not samurai; it’s tigers! Let’s take a look at the four tigers on the left. What do you notice about the tigers? The title of this work is The Qing Army’s Foolish Plan of Using Tigers as Weapons, and these titular tigers are, in Shōsō’s telling, being sent by the Chinese as an attack ploy. As you might realize, there are some problems with this scheme. Tigers, however ferocious they might be, will not win against muskets and bayonets. But the point of this piece is precisely to present the Chinese military as bumbling and cowardly. The message you take away is something like: the Chinese are too scared to come and face us themselves, and too stupid to realize that tigers wouldn’t work on us.

At the time, China was also undergoing modernization. Like Japan, it had suffered humiliating defeats to European powers during the Opium Wars and had embarked on the so-called Self-Strengthening Movement in response. But unlike Japan, this effort was marred by corruption and mismanagement, so that when the Sino-Japanese war broke out in 1894, the Chinese military was still relatively antiquated. In that sense, the tigers are a metaphor for the Chinese military as a whole: the Chinese troops were disorganized and fighting a battle they couldn’t win. The Japanese would parlay their military advantage into eventual victory, announcing their presence on the global stage as the prime power in East Asia.

Next, I want to talk a little about the medium of this work and how it was made. Does anybody have any guesses as to the medium? Although it appears to be a painting, the piece is actually a color woodblock print of the Nishiki-e style, which was invented about a century earlier. Here’s how a woodblock works: first, an artist designs an image on paper. The paper is pasted on a cherry wood block, and a carver chisels to create the original in negative, with the areas to be colored raised in relief. Then, they coat the surface of the woodblock with ink , and apply pressure to a piece of paper laid over the board to make a print. For a print with multiple colors like this one, a separate block is carved for each color, and they’re pressed one at a time.

And this is not a meaningless distinction! Unlike a painting, woodblock prints can be cheaply mass produced, depending on the block, potentially thousands of times before the carvings wear off. That makes them ideal for propaganda artists who are trying to reach as many hearts and minds as possible. For that reason, woodblock prints glorifying the Imperial Japanese Army soared in popularity during the war. The conflict lasted just nine months, but over 3,000 prints were produced during this time. And it’s easy to see why: black and white photographs were around, but it’s hard to capture the drama of war without the bright colors and exciting scenes of these prints.

This propaganda had two audiences. First, domestic consumers within Japan, but second and more importantly, foreign powers who had considerable sway in the region. For instance, almost all of the warships used by both Japan and China were built by either Britain or France, and Japan exported huge volumes of art to those same powers. It even created a public corporation and an exhibition bureau to promote exports and maintain quality standards. With this context, I think it’s clear that a work like this, which highlights the contrast between Japanese discipline and Chinese cowardice, wasn’t done for fun. Instead, it was part of a calculated strategy meant to build financial and diplomatic support for Japan in the places with the most power and influence.

That’s all I have for you today—I hope you learned a little about the way art and war can intersect. Maybe the Qing didn’t use tigers as weapons, but the Japanese were certainly not foolish when they chose to turn art into a weapon of their own. Thanks.